The history of Pencarrow

The Memoirs of Beryl Teague

Written in 1991, Beryl recalls Pencarrow in the late thirties.

When the rich were very very rich and the poor, very very poor, people had large families. Work was very hard to come by; no work, no money, if one was lucky enough to have a job, you just worked very hard to keep it.

Most girls, if they were lucky went into Gentlemen’s Service. These situations were not normally advertised, one got in through recommendation. Myself, I had an Uncle and Aunt who worked at Pencarrow. Uncle Percy was a gardener, in charge of the lawns and flower beds, of which there were many. Aunty worked in the laundry.

Somehow my memory is a blank, concerning the day I actually came to Pencarrow. It was directly after Christmas 1934, I can just recollect my dad walking with me, from our little cottage at Sladesbridge to Pencarrow, with him carrying my suitcase.

My position on the staff was Under-House Maid; really I was just a servant to the servants, a position I did not at all like. My wage was £18 a year, paid monthly by Sir Hugh himself. Each of us went in turn to his study to collect our wage packet; our National Insurance stamp was 1/6.

Uniforms were a must and these we had to provide ourselves. In the mornings we all wore blue dresses, large white bib-aprons, white caps, black stockings (not nylon – horrible lisle), fully fashioned with seams, low heel, one bar button fastening shoes.

The kitchen and scullery maids wore this uniform at all times. The Cook, the Housekeeper, Mrs Coombs, wore all white, dress, apron, no cap, large white belt, with a bunch of keys always dangling.

In the afternoons the three House Maids and Parlour Maid wore black dresses with small dainty aprons, with white collars and caps to match. The Parlour Maid wore white cuffs, this made the distinction. Later this changed. While I held the position of Parlour Maid I was asked to change my dress from black to green. This was impossible for me because I could not afford it, so Sir Hugh bought me a green dress, much to the annoyance of Clara and Mrs Mathews!

The House

Now to the house. Pencarrow was really riding on the crest of the wave before the war in 1939. Sir Hugh Molesworth St-Aubyn, the 13th Baronet, lived there, with his son Mr Hender and Sir Hugh’s friend, Mr Cately, a lovely gentleman, very tall, distinguished, quiet and almost blind. Sir Hugh was a lovely gentleman and became a little eccentric after his wife died; he just hated visitors and loved doing things in his own time and his own sweet way. He always carried a notebook and pencil; everything was written down and entered into his diary each day. Every day he went to the garage and read the petrol gauge and mileage on his two cars. Wish I could remember what make the cars were.

When Sir Hugh’s wife Lady Sybil died, he left the main bedroom and her boudoir just as she had left it. He himself moved into his dressing room and her Ladyship’s room became a shrine. Clara and Mrs Mathews, lovingly cleaned and cared for it.

Every room in Pencarrow was furnished except for one room, which we called the attic.

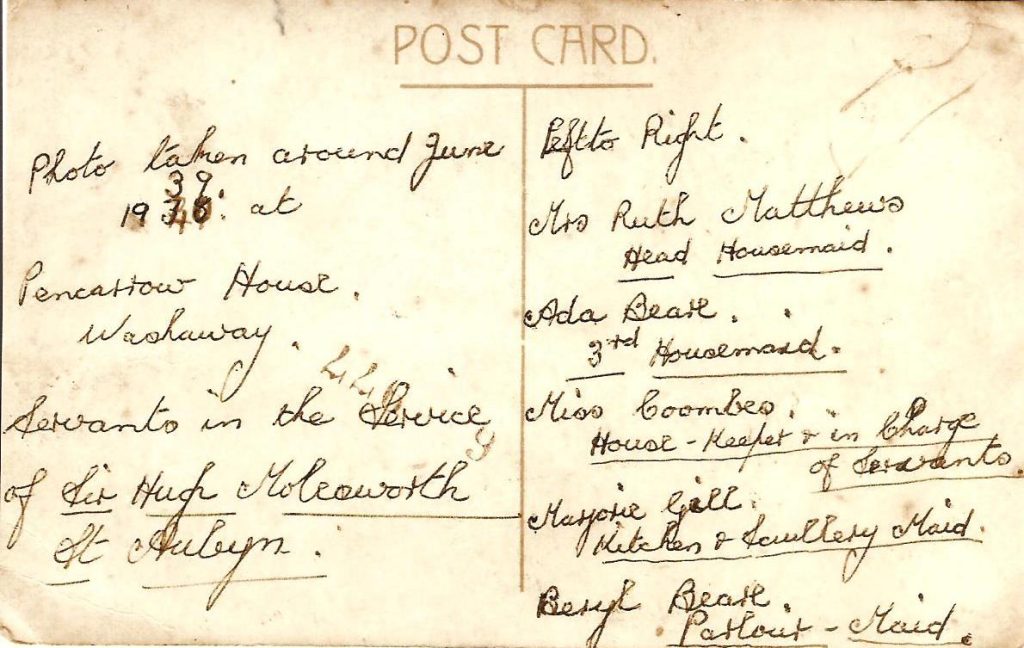

The staff indoors were eight in number:-

Mrs Coombs Cook/Housekeeper – a real battle-axe

Mr Dustow Butler/Valet – truly a gentleman’s gentleman

Mrs Mathews Head Housemaid – practical lady, rather nosey

Clara – My friend, Supervisor and Boss

Parlour Maid

Under House Maid

Kitchen Maid

Scullery Maid

Willy Abbott was our Handyman; he cleaned shoes, stoked and kept two huge boilers going in the cellar. These boilers were kept going day and night. One supplied all our hot water, the other the radiators, which were placed all over the house. Pencarrow in those days was a very warm house. Willy also brought in fuel and lighting sticks for the Cornish range and Aga, which was in the kitchen. Also fuel, logs and firelighters for our grate upstairs, which was lit every afternoon. Sir Hugh’s grate, in his study, and the grate in the entrance hall, the fire in that grate was lit each afternoon.

Another of Willy’s jobs was to take all the hampers of cloths to and from the laundry. Two ladies worked four days a week in the laundry: two days washing–all by hand–then two days ironing. These hampers were huge and on wheels, all the linen from the beds was white, huge damask table cloths, towels, all our caps and aprons were starched. Besides all the household linen there was Sir Hugh’s, Mr Hender’s, Mr Cately’s personal clothing, not forgetting all the servants’ clothing.

Those two ladies worked so very hard. When those hampers came back every Thursday afternoon, Mrs Mathews and Clara sorted everything; the gentlemen’s clothing was carefully scrutinized, anything to be repaired was put to one side, buttons, etc, Clara would see to and the rest was put aside for the sewing lady, a Miss Salmon, who came one day a week to do the darning. I have never seen such beautiful darning, it really was a work of art. All our clothes were sorted and placed on our beds.

Life in the House

Our working day – the junior staff had to be downstairs by 7.00 am. We made a beeline for the kitchen for a quick cup of tea, then on to our duties. The Under Housemaid’s first job was to clean the grate in the library. Clara would then use the carpet sweeper and dust. The electric vacuum cleaner was very rarely used. The Parlour Maid opened all the shutters, including the Butler’s Pantry. Mrs Coombe came down at 7.30 am. The kitchen staff cooked the servants’ breakfasts. Clara took morning tea trays to all the gentlemen.

Our breakfast was at eight in the Servants Hall. We were called to meals by the ringing of a handbell, loud and clear, by the kitchen maid standing at the bottom of the granite steps. Our breakfast, two slices of bacon, fried potatoes, two slices of toast with butter and marmalade. Meals were very proper, Mr Dustow at the head of the table, Mrs Coombe to his left. Our dinner, midday, always consisted of a joint, sirloin of beef, leg of port, leg of lamb, and sometimes cottage pie. Fridays, always fish, beautiful cod steaks.

The plates and meat were always placed in front of Mr Dustow, who carved, then each plate was handed to Mrs Coombe, who served the vegetables. You were served in order of rank. The elder servants carried a little conversation, not much, we as juniors never spoke unless we were spoken to. This was a rule which the young servants had to obey and we were very much “yes people, not allowed to have an opinion of our own. We bowed and scraped to our senior servants. The Parlour Maid was the only one having any close contact with the gentry.

Every time we spoke we had to give the person who was speaking to us their title, not once, but with every sentence. The Scullery Maid’s job was the worst of all. She washed every dish that was used in the kitchen, including all the pots and pans, which were endless, all the dishes from the Servants Hall had to be carried to the scullery and the china from the dining room. She washed everything in two huge lead sinks. Once everything was washed and dried, everything had to be put in place back in the kitchen. The scullery floor bottom larder, inner larder and passage was all blue slate, which was scrubbed in turn once a week and washed daily.

The Housekeeper’s room also had to be scrubbed weekly and the granite from the bottom of the steps to the back door. Poor dear, she spent an awful lot of her time on her knees scrubbing. Of course, she had a kneeler and wore a huge hessian wrapped apron around her waist. The grate in the Housekeeper’s room was her responsibility and that was cleaned and black leaded every day and the fire was always lit in the room at midday. More than likely she would have cleaned a lot of the copper pans in the kitchen, the shelves were lined with them. She would also have cleaned and prepared all the vegetables.

Duties

For the Kitchen Maid she danced in attendance to the cook; fetched and carried, cleaned the kitchen–the floor was red tiles. There was one very large kitchen table, placed length-wise in the middle of the room. Another smaller one in front of the window, both white wood, which again was scrubbed. The Cornish range was cleaned, black leaded and lit daily and the Aga cleaned and re-fuelled.

These two girls would have completed the hardest of their work by 2.30 – 3.00 pm, they were then allowed to go to their bedrooms for a rest, wash and change into clean uniforms, returning to the kitchen again about 4.30 pm to prepare tea for the dining room and servants hall. The cook also retired to her bedroom about 2.30 pm for a rest and change. She always took tea on a tray in the Housekeeper’s room.

The two senior Housemaids daily task was to keep all the bedrooms and downstairs rooms cleaned and polished. Clara had a cupboard on Sir Hugh’s landing, that was used for storing all their cleaning materials. It also contained a sink with draining board to which hot and cold water was supplied. All the staff had their own work boxes. They were made of tin, black enamelled, with a carrying handle. In these boxes, we kept all our individual tools, cleaning materials, dusters, polishes, etc.

Bathrooms for the gentry were also on Sir Hugh’s landing, and again were the responsibility of Clara and Mrs Mathews for cleaning etc. When visiting ladies stayed overnight, Clara had to lay out their evening clothes, help them dress for dinner and when they went down for dinner she would turn the beds down and lay out their nightgowns etc.

The Under Housemaid, a position I held myself for a while, was not an interesting job at all. She had to make all the servants beds, change the sheets etc once a week. The servants’ rooms had washstands with jugs, basins, soap dishes and the dreaded chamber pots, which of course, were used nightly. We had only one toilet which was at the far end of one landing, next door to the Housekeeper’s bedroom, which we dare not use during the night as to turn on a light at night was a crime. We all had candles and matches in our rooms.

So it fell to the Under Housemaid to keep all this china clean. She would carry a slop bucket from room to room, emptying the washbasins and chamber pots. She had a Housemaid’s cupboard at the end of one landing, with a sink and drainer, so all this china had to be carried down daily and washed, the jugs filled with clean water. She also had to clean all the servants’ bedrooms, landings, bathroom, toilet and the back stairs, which were painted dark brown and so showed all the dust (Lady M has inserted here that it was lime).

The bedroom floors and landings were all covered in brown lino. Our workroom, she also had to clean. We had a grate in that room, in which a fire was lit just before we went to tea, so the grate was cleaned daily and it was her job to bring up from downstairs all the lighting sticks, coal and logs. This little room was dark and dingy. One had to stand on a chair to look out of the small window, but it was our haven. In the evenings, especially wintertime, everyone except Mrs Coombe and Mr Dustow, met in this little room when they had finished their duties downstairs after tea.

We all had a cane armchair each and we sat around the fire, mostly enjoying each other’s company. It was the only time of the day we met privately and could talk to each other in our own language. Some of us would knit and sew but it was an hour of freedom. When the clock struck seven, the kitchen staff left us again to return to their posts in the kitchen.

Dinner

The evening meal for the gentry had to be cooked now and the Parlour Maid left at seven-thirty to take up her post in the Butler’s Pantry. Firstly she sounded the gong and this was the signal for the gentry to dress for dinner. Then she would go to the kitchen to read the menu, which by this time, the cook would have written and hung on the kitchen dresser. She then selected the china plates and dishes, which were kept in the kitchen cupboard and placed them on the rack over the Aga. Then she would have to go back to the Butler’s Pantry and collect what silver dishes would be needed for the meal and so take them back to the kitchen and stack them neatly on the rack.

When I held the position as Parlour Maid I enjoyed the job very much, working with the Butler, Mr Dustow, was indeed an education in itself. He was very much a gentleman’s gentleman, so very proper and correct. I have always been very grateful for what he taught me. The dining room table was his pride and joy. For breakfast, we always used a white damask table cloth, so when we cleared the breakfast and the cloth was removed, he would clean and polish the table, a job he would not allow me to do.

First, he cleaned off the grease with a cloth wrung out in cold tea and vinegar, then he would polish it and so lay the table for lunch. Place-mats were used for lunch and dinner. The centrepiece for lunch was a bowl of flowers on a stand. The dinner table always carried a display of silver which was brought up daily from the vault in the cellar. He varied it from day to day.

Serviettes, of course, were white damask, rolled and placed in silver rings for breakfast, folded into boat shapes for lunch and dinner. The silver, of course, we cleaned daily in the Butler’s Pantry; a green baize cloth was first placed on the table to avoid scratching or damaging any of the pieces. Naturally, we cleaned what was used daily and a certain amount was brought up each day from the vaults. When I first saw the vault, I compared it to Aladdin’s Cave. It was alright going down there with Mr Dustow but another thing whenever I had to go down there alone. The only time I would have to, was when Mr Dustow was on holiday.

The massive door of the vault was unlocked by a secret combination. My greatest fear was going in there alone and the door slamming shut behind me. My other duty taking me to the cellars daily was to clean the knives, of which the handles were solid silver and the blades steel, so these had to be inserted into a knife machine which, when I turned the handle, would clean the blades. The other chore was to fetch water from the well for drinking – we never drank water from the taps – so I filled a pitcher daily for the dining room and the kitchen-maid did likewise for the servants’ hall.

Mr Dustow always cleaned Sir Hugh’s shoes. Willy would clean Mr Hender’s and Mr Cately’s. Again Mr Dustow took it upon himself to clean and polish Mr Hender’s riding boots; he made them shine to such an extent that you could almost see your face in them. The gentlemen’s evening suits and any clothes worn the previous day would be brought to the Butler’s Pantry to be brushed and cleaned and very neatly folded and then taken back upstairs to their rooms.

We, of course, washed all glass and silver in the Pantry. Great care had to be taken, especially whilst washing, so we used wooden troughs placed in the sinks. Every morning, very soon after breakfast, Sir Hugh would have a formal interview with all his heads of staff, starting with Mrs Coombes, followed by Mr Dustow, Mr Salmon (the Steward), Mr Linden (the Chauffeur), Mr Davey (Head Gardener). The last three gentlemen always came a few minutes early for their appointment and so came into the Butler’s Pantry and had a few minutes chat with us; this was really the highlight of our day, contact with someone outside the four walls of the house.

(Page missing…….. then goes on……..)

The gardeners would pick me a nectarine; the taste I can still remember, ripe, full of juice, still warm from the sun. Nothing I have ever bought from the shops since has tasted like the ones from Pencarrow.

Once a week the Fishmonger called, the Butcher twice weekly. Mrs Coombe would telephone her orders through to them. A pig was killed and brought into the kitchens to be cut and salted twice a year. I rather think they came from Mr Lobbs’ farm at Washaway. Mrs Hoskin, the lady who lived in Camp Cottage (Frances’ cottage) always came and helped with salting. Milk, cream and eggs came from Trescowe Farm. The groceries, of course, were bought in bulk form; sacks of flour, sugar etc, tea chest of tea, always delivered. Not having worked in the kitchens I don’t know the suppliers. We kept to our own domain.

One of my younger sisters Eileen worked at Pencarrow as a Scullery maid for twelve months. She left, never having seen the front of the house where the gentry lived. Last year she came as a visitor and I showed her the house she had lived in and had never seen except for the kitchen area, backstairs and her bedroom.

Changes

Myself, I left Pencarrow at the end of September 1939. War had broken out, we all thought we were going to be killed, so my boyfriend and myself decided we would get married. I had the princely sum of £50 in my Post Office Savings account, my boyfriend even less. He was a plumber, working for Mallett & Son in Wadebridge. We married at Egloshayle Church on October 4th 1939; nowhere to live so we moved in with my parents in their little cottage at Sladesbridge. We were bursting at the seams, my husband being six years my senior when his age group came up and he had to sign up for War Service but because of his trade he was deferred.

Sir Hugh let us have the very next cottage that became vacant at Sladesbridge. We moved into our new home in March 1940. My husband had his calling up papers for the Army in August 1942; by that time we had an eight-month-old son.

I made regular visits to Pencarrow until Sir Hugh’s death in (I think) January 1942 and on the Sundays, Sir Hugh went to Egloshayle Church, he always stopped on the way home and called to see me. After Sir Hugh’s death, I lost contact with Pencarrow. When it was opened to the public in 1975, I just could not wait to get back. First I wrote to Joan Colquitt-Craven, asking if there was any vacancy for a job. She promised to call and seem, sometime when she was passing.

The weeks passed, no Joan, so one Sunday, with friends we went to Pencarrow as visitors. We walked through the front door, paid our entrance fee (to Joan who was sitting at the desk). We were told to go into the Music Room and wait for a guide. Joan had no idea who I was as we had never met officially.

My eyes, as you can imagine, were everywhere and I could not believe what I was seeing. One remembers things as they last saw them. My first reaction was, where has all the shine gone? In our time it was like the Army, spit and polish; you did not just shine things, you polished until everything shone back at you, especially the grates. In every room, we had steel fenders and steel fire-irons, which we cleaned and polished until they looked like silver.

Pieces of furniture were missing and the lovely rich carpet upstairs on the front landing was gone. Naturally, the furniture was re-arranged for visitors to walk through the rooms. Going back to our wait in the Music Room, our guide finally appeared and started the tour. I just stood in utter amazement because I could not understand a word of what he was saying, so when we came back into the entrance hall I quietly went over to Joan and introduced myself.

We had a lovely chat and so I continued with the tour, interesting myself with what I was seeing. I blocked out the guide, who I found out later was Mr Bone. The very next day, to my utter delight, I received a telephone call from Joan saying how very pleased she was to have met me and asking me if I would be one of her guides. Well, I was over the moon, just could not believe my luck. An appointment was made for me to come to Pencarrow to discuss my duties etc.

New Duties

On the given day I arrived at the back entrance as I was instructed. Ongoing through the big arch into the back courtyard, I immediately felt like an intruder, as a family were gathered having a picnic lunch on the grass (which is now the children’s play area). At that time I had not met Mrs Arscott Molesworth St-Aubyn (as she was then), or her family. The last time I had seen the Colonel he was a boy of 13 years old. A lady stepped forward, seeing me hesitate, asking she could help me. I explained who I was and my reason for calling. She told me Joan had not yet arrived and would I like to take a seat and would I like some lunch. I took a seat, refused the food and of course, my brain began to tick over time.

My curiosity soon got the better of me and I asked that lady if she was Mrs St Aubyn. The answer, of course, was yes, and I was introduced to her family, William, James, Emma and her niece, Georgina. James was so much like his dad was as a boy and it was lovely meeting them. I warmed to them immediately, especially Mrs St Aubyn. It was much later that I met the Colonel; seeing him last as a 13-year-old and now almost 50 years old, was an experience. Somewhere, deep down inside me, there is a bond, I feel; I want to mother them, love them and help them.

As regards the house, the worst was yet to come for me. When Lady St Aubyn showed me the servants quarters, both downstairs and upstairs, well I was horrified. It was an utter and complete mess. All our bedrooms were derelict and empty, also the lovely rooms in “Piccadilly” likewise. We used those rooms for night nurseries when the children came to stay in the summer. It echoed children’s voices, with their Nannies and Nurse-maids; Clara and Mrs Mathews lovingly cleaning all those lovely rooms. Now to see them empty and derelict–it was more than I could take. Secretly I have broken my heart over Pencarrow. As we, the working class, have gradually come up and have more, these big estates have gone back. When I left Pencarrow in 1939 I quite thought that it would keep that standard forever, so it was indeed a very big shock to find it so very run down.

This is where I wanted to cushion the family as it were, I just could not accept the fact that Colonel and Lady St Aubyn were actually working manually. Lady St Aubyn with a “pinny” on, her sleeves rolled up and the Colonel planting and gardening and going into the house by means of the Scullery door; well, I looked at them in disbelief. I wanted to send them to the bathroom, let them change into their best clothes, put them in the front of the house and wait on them. I still want to care and look after them.

When I look back and recall how we used to wait on Mr Hender, his work took him to Plymouth each day. Clara called him each morning with his morning tea, then ran his bath. Mr Dustow helped him dress, kitchen staff cooked his breakfast, I took his breakfast to the dining room and Mr Dustow would serve it to him. Mr Linders, the Chauffeur would bring his car to the front door, ring the bell and Mr Dustow would then see him to the door, carrying his hat, overcoat, umbrella and briefcase. This was the lifestyle I knew of the gentry, so you can see how hard it was for me to adapt to Colonel and Lady St Aubyn’s lifestyle today. They are such a hard-working couple, my heart goes out to them. It makes me wonder sometimes, is it worth it all. Myself, I still find it very difficult to come to terms with visitors in the house and gardens.

Life

One must appreciate that we, as junior servants, were not allowed to walk in the grounds and could only use the entrance to and from the servants’ back door. When the weather permitted, afternoons, we would go up onto the roof, to get some fresh air. We never saw much of the outside world. Our time off was one afternoon a week. The Housemaids were the lucky ones, changing directly after their midday meal and leaving the house.

The kitchen and pantry staff had to serve and clean up from the gentry’s lunch before we could even go into our rooms to change. There was a rule to be indoors by 9.00 pm; if not, Mrs Coombe would lock, bolt and put the chain up on the back door, then, of course, we had to ring the bell and wait, like a naughty child, until she unlocked it and let us in. I did not finish there; we would then have to go to her room and give an account of why were late.

Every alternate Sunday afternoon we had off, but 1 ½ hour break in the morning. Once a month, Sir Hugh allowed the Chauffeur to take the car and three servants to Bodmin. This was indeed a treat, although, for us, our turn did not come often. Mrs Coombe always went, with either Clara or Mrs Mathews, leaving just one seat vacant for a junior member of staff and if you were lucky enough to be chosen and you had sixpence in your purse, one shilling at the most, you felt rich. The only shop we went into was Woolworth’s. In those days everything in the store was priced 3d or 6d, that, of course, was old money. We would walk around that store many times before we eventually bought something.

Church

On our Sunday mornings off, Sir Hugh expected us to go to St Conan’s Church. We then walked the drive and always came off at the gate on the right, crossing the lane, into West Downs and from there a lovely church path through the woods to the Church. Gladys and myself were both Confirmed at St Conan’s in 1936.

The first time Sir Hugh took Gladys and myself to Egloshayle Church with him, we both felt like Queen Bees driving to church with Sir Hugh in a chauffeur-driven car. All went well until we went inside the Church and sat in the wrong seats. Unknown to us, there were special seats for the gentry and servants of Pencarrow. Unfortunately for us, we sat ourselves down in a pew that belonged to Mr Phillips of Court Place. The Church Wardens asked us to kindly move. Sir Hugh witnessed this and later was called to his Study, on the carpet, and severely reprimanded.

Everyone in those days had their special pew in Church. We were young and so full of our own importance, coming to Church with Sir Hugh, thought we could sit anywhere – how wrong we were. Sir Hugh explained he would rather we had sat with him than gone into Mr Phillips’ pew.

The postman called at Pencarrow twice daily (Mr Luke), a lovely gentleman, living at Washaway in the little cottage at lane-end opposite the phone box. Mr Luke, his wife and sister, ran the Post Office. These people were the salt of the earth; honest, kind, friendly, clean, uncluttered people. Mr Luke, an ex-Naval man, tall, dark, and must have been very handsome in his day; his face used to shine and he had a wonderful smile.

These two ladies were so clean and well-scrubbed, hair cut very short, worn straight in a neat bob. They wore flat lace-up shoes, lisle stockings, tweed skirts and always pinafore aprons, nothing with any string or bows. Their only means of transport was a bicycle and they had one each. Mr Luke delivered our mail every morning at 7.00 am; there was a panel cut in the back door at Pencarrow and Mr Luke had a key.

Every night before she went to bed, Clara would place a chair under the panel, so when he unlocked it he would place the mail on the chair. Any outgoing mail would be placed there, with the necessary money for postage. Sir Hugh, had an account, of course, which was paid monthly. Afternoons, Mr Luke called again about 4.00 pm and this time he rang the back doorbell. Mr Dustow and Clara would then go and have a chat with him; mail again, collected and delivered.

Mr Luke had Thursday afternoons off, so as Parlour Maid I had to cycle to the Post Office those afternoons to collect any mail and the Guardian. On one such afternoon, Sir Hugh gave me a £5 note with an order for Postal Orders etc. That was when the £5 notes were big white tissue paper style. Having never seen one before, I went off that day feeling like a millionaire.

Rodents

I must tell you about Pencarrow RATS. One morning there was one almighty commotion when Sir Hugh went to take his morning bath, his bath soap was missing. It was sheer uproar, everyone was questioned in turn. No one had taken the soap. We were all under suspicion. Then one morning as I walked through the inner hall, on my way to open the shutters, there was the soap. It had been gnawed and broken into pieces, by rats, of course, all scattered along the green carpet. It was decided that poison should be put down, so before retiring at night Clara put down the prepared poison. This was done until it wasn’t eaten anymore.

Much later, one morning, “Hoey” our kitchen boy, came down looking as white as a sheet, saying he had seen a rat in his bedroom. Of course, that was fine fun for us girls, we all laughed and told him it was a mouse. He got very angry and said he knew a B——- RAT when he saw one. A few days later Gladys, the Under Housemaid, went into the servants’ bathroom to clean the bath when out jumped Mr Rat. Her screams brought everyone running, but the rat escaped – we never found that one.

It was I who was to encounter rat number three. Every day after we had our midday meal, I collected all the scraps from the dinner plates for Sir Hugh’s dog. I would take the scraps to the scullery. In no way was I allowed to go through the kitchen, I had to go out the back door and walk around to the scullery, where we kept a big full of dog biscuits. These I mixed with the scraps. Normally I would put the lid sideways and so put my hand in and take the biscuits from the bag. On this particular day I took the lid off and there was the biggest rat I had ever seen. She had made a nest and was sitting there waiting to have her babies. I don’t know who was more surprised, me or the rat! Of course, I screamed, which brought Mrs Coombe, Joey and Margery running from the kitchen. They all looked at the rat. Joey grabbed a sweeping brush; Mrs Rat had other ideas, jumped out and ran, disappeared down a hole under the ledge outside the scullery door.

These are just a few of my early memories of Pencarrow, most probably there are more locked away in my memory box, it’s digging them all out!

(There’s much more history at Pencarrow, take a look at the stories here.)