The history of Pencarrow

Sir William Molesworth

Early Years

Sir William Molesworth, our 8th baronet, was born on 23rd May 1810 in London, the oldest of six children. Not much of William’s childhood was spent at Pencarrow however visits were recorded in 1812, when the house was ‘not furnished yet’ and in 1817. There were also further visits in subsequent years, with the family only staying a few weeks at a time. William’s father, Sir Arscott Molesworth, was a keen huntsman so instead the family spent most their time at their other estate, Tetcott, on the Devon/Cornwall border.

William had ill health throughout his childhood and suffered from a condition known as the King’s Evil or scrofula. This resulted in fevers, swellings and infections of the lymph nodes, which produced disfiguring ulcers in his throat, ears and neck. William said of his childhood ‘my schoolfellows made sport of me and allowed themselves to use language which cut me to the soul in reference to my deplorable infirmity’. He was sent to boarding school in Putney, saying of it in later life that he was ‘ill-cared for and negligently taught’.

Education

His father had intended William to go to Eton following his footsteps and those of his grandfather. However when William was fourteen his father died (December 26th 1823) and his mother, advised by Dr Lecke, decided not to send him to Eton but to be educate at home. Dr Lecke’s letter enclosed a ‘scheme’ of lessons with Greek and Latin every day, Latin or English composition every day, French one hour per day, Bible studies daily, history to be read during the week and examined on Sunday, drawing every other day and Greek on Sundays with Mant’s Bible. A tutor, Mr Bartholomew, was engaged and William left the school in Putney in 1824.

William’s mother Mary Brown was from Edinburgh and had family connections there – David Hume the philosopher was a relation and the Munro’s, later to be well-known through Sir Hugh Munro of Munro’s Tables. Mary as a widow with five children (Caroline had died only six weeks after her father) decided to go back to her home city. A lease on a house was taken in New Town and the family lived at 97 George St for the next six years.

William continued his studies with his tutor, following a programme that began at 6.30 am with Botany and ended with Law at 11pm. He allowed himself half an hour for breakfast and a longer break from 3pm to 6pm for dinner, but nevertheless his timetable was rigorous especially by present day standards.

William’s Later-Teens

By 1826, William aged just sixteen was attending lectures in the University of Edinburgh developing his interests in Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, Botany and Chemistry. According to his mother, the professors (John Leslie an eminent mathematician, Thomas Hope Professor of Chemistry, Robert Jameson Professor of Natural History) ‘took a liking to William and treated him not as a boy, but as an associate’. He was also permitted to use the university library and began accumulating his own library purchasing works of ‘authority and instruction’.

In 1827 William went up to Cambridge to St John’s, the college his father and uncle had attended. Though he was not happy there, finding his studies undemanding and the mathematics lecturers knowing less than he did! He moved to Trinity College where he had more friends and acquaintances, including friends from Cornwall.

William did not graduate from Cambridge. In 1828 he took up the cause of his friend, Edward Duppa who had been sent down following involvement in an unlicensed gambling party. William challenged Duppa’s tutor to a duel believing he had been insulted. The affair became public and the Mayor of Cambridge summoned both William and the tutor Henry Barnard to appear before him resulting in his college expelling him.

Travelling

William’s mother decided this would be a good time to undertake the ‘Grand tour’ travelling in Europe and in August 1828. He went with guardian Sir Joseph Stratton, a retired military gentleman, and set out for Germany. William took lodgings for two months in Offenbach, a town close to Frankfurt, studying German and French. He then moved to Munich, continuing with his studies, and enjoying social occasions such as balls.

However the unfinished business of the duel still loomed, as William felt obliged to honour his challenge. With his man servant Duncan McLean he travelled 700 odd miles in a fortnight from Munich to Calais where the duel duly took place on 1st May 1829. Neither William nor Barnard sustained any injury and the account William sent to his mother [letter dated 2nd May] said briefly ‘I am happy to inform you that I am alive and well. I could not hit my adversary, do all I could’.

Return To Britain

William then continued his travels going to Florence and Rome, then Naples. He continued to work on languages, adding Italian and Arabic to French and German, and practising such accomplishments as fencing, drawing and painting. By 1831 he had begun to make his way back to England reaching Pencarrow on 5th April 1831, a few weeks before his twenty-first birthday.

The Reform Bill was dominating Parliamentary business, and when it was defeated in the committee stage, a general election became inevitable. William’s radical philosophy drew him to politics, though he would not be old enough to stand for Parliament until after his birthday on 23rd May that year.

Following his return to Pencarrow, William devoted time to establishing the Wadebridge-Bodmin Railway company. He engaged Hopkins the civil engineer to survey the land for the route with the prospectus for the formation of the Railway Company drawn up by Mr Woollcombe, from the family’s firm of solicitors.

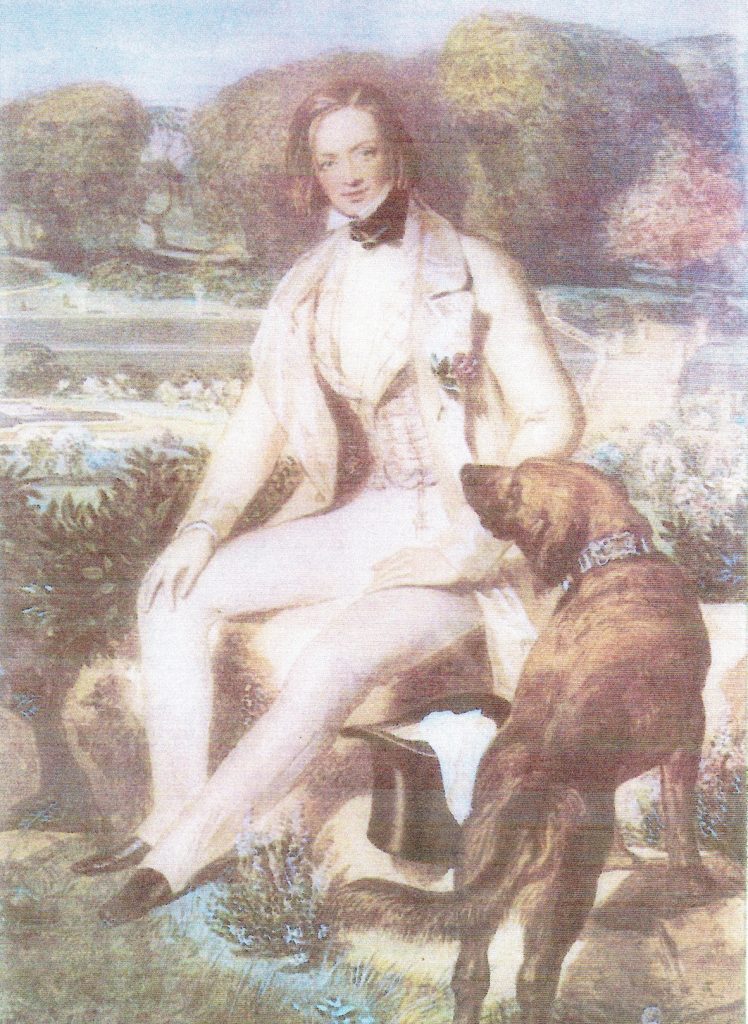

Sir William, aged 23, is described by Mrs Grote, the wife of his friend and fellow MP, as having ‘A pleasant countenance, expressive blue eyes, florid complexion and light brown hair; a slim and neatly made figure about 5ft 10inches in height with small, well-shaped hands and feet’. [The Philosophical Radicals of 1832, Comprising the Life of Sir William Molesworth by Mrs Harriette Grote]

Later Years

1835 Sir William was again elected unopposed for East Cornwall. As MP he had joined a group named the ‘Philosophical Radicals’ who advocated various reforms such as universal education, disestablishment of the church and universal suffrage. The Reform Bill had abolished ‘rotten boroughs’, those constituencies ‘in the pocket’ of landowning families where voters were almost non-existent and those who could vote, received bribes.

Sir William’s radical views attracted the disapproval of the electorate and local landowning families, as well as his uncle William, who was Rector of St Breoke Church. His radical position affected his personal as well as his public life. William hoped to marry Julia Pole Carew from Anthony but her uncle Lord Lytton refused permission for the marriage.

In 1837 Queen Victoria came to the throne and Parliament was dissolved on the accession of a new monarch. Having alienated his Cornish electorate, Sir William stood for Leeds and was duly elected. He was accompanied at the hustings by Woollcombe, now a friend as well as his solicitor.

Four years later at the General Election William did not stand again, having quarrelled with his Leeds constituents due to his views, this time on foreign policy. He retired to Pencarrow occupying himself by work on the gardens.

The Pencarrow Gardens

William designed the Italian Garden with a fountain and sunken flower beds; he constructed the rockery, grotto and glass houses with the latest heating systems. He made the mile-long drive that runs through an early English encampment and ancient woodland. Planting extensively including specimen trees from the Americas, one of which the Araucaria araucana acquired the common name ‘Monkey Puzzle Tree’ at Pencarrow after Sir William’s guest Charles Austin commented ‘that tree would puzzle a monkey’.

In 1844 William married Andalusia Temple Grant, a widow whom his family and friends all considered not his equal in status. Andalusia had studied at the Royal Academy of Music, and had subsequently sung in operas at Covent Garden and Drury Lane. Aged 18 she met her first husband, 60 year-old Temple West. They were married in June 1831, at St George’s Hanover Square, a church favoured by the fashionable rich. Temple West died eight years later of apoplexy, Andalusia becoming a relatively rich widow. It is not known exactly when William met Andalusia, but she is mentioned in his diary in early April and they were married three months later.

Further Political Activity

Against the political background of the Irish potato famine in and demands to repeal the Corn Laws, in 1845 William was elected to represent Southwark in a by-election. He remained MP for Southwark for the rest of his life.

It was in 1853 that Sir William joined Lord Aberdeen’s government as First Commissioner of public works, with a seat in the Cabinet. This position gave him ‘charge of the Royal Palaces, all public buildings and offices…the parks of the metropolis…and the public gardens at Kensington, Kew and Hampton Court’. [Letter to his aunt] As Commissioner, he introduced Sunday opening for the public at Kew Gardens, and Kew has continued to open on Sundays since that time.

By 1855 Sir William had became Colonial Secretary after the resignation of Lord John Russell in July, who avoided a motion of censure on the conduct of the Crimean War. However William’s health, which was always poor, became a cause of concern. Andalusia though did not feel it bad enough to call a doctor however his sister Mary finally prevailed upon Andalusia to summon Elliotson his doctor of twenty years, but it was too late. Sir William’s could not withstand gastric fever and he died on 22nd October in London. Though he himself had expressed a wish to be buried in ‘a favourite spot in my grounds under a clear sky’, his grave, in which Andalusia was also buried after her death in 1888, is a mausoleum in Kensal Green Cemetery, Paddington.